Power, labour and environmental justice conflicts in the ecosystem service provision.

By Joachim Spangenberg.

The concept of ecosystem services (ESS) has become almost mainstream in academic and political statements (although not yet in practice), but it suffers from one severe deficit: it is a-social, human activities play no role in it except as ESS beneficiaries.

What is “ecosystem services”?

The most frequently used definition of ecosystem services is “Ecosystem Services are the goods and services that biodiversity and ecosystems provide to human well-being” (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005). This is an “objective” definition: the services are provided by nature, with no human involvement mentioned; neither the valuer nor the beneficiary play a role in it, and providers do not exist. If those considered to be beneficiaries value (recognise and welcome) the effect of nature, if they actively mobilise, passively enjoy or reluctantly bear it plays no role. The decision what is a (dis)service has to be taken by experts and authorities.

Alternatively, an economic definition, i.e. one based on subjective values, has been suggested:“Ecosystem Services are the benefits humans recognise as obtained from an ecosystem and that support, directly or indirectly, their survival and quality of life” (Harrison et al. 2009). In this view, economically speaking, what is not recognised cannot be demanded and has no value. It is no ESS.

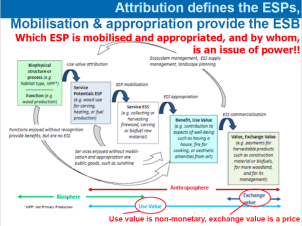

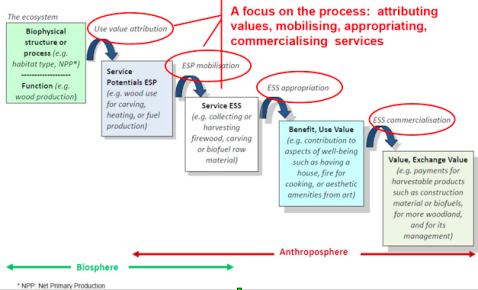

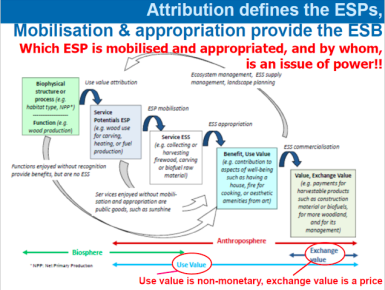

The revised ESS Cascade

In reality, however, it is human who define, mobilise, appropriate and commercialise ESS. Their first step is to recognise that an element of nature might be used for any purpose (Use Value Attribution & ESS Potential Identification). Different groups, agents, stakeholders and cultures have different world views and thus recognise different potential services.

Identifying use potentials is an intellectual act, not (yet) a physical intervention. Nonetheless it change the character of a piece of nature into a resource, and competing potential beneficiaries will fight about who determines what happens to that piece of nature. For instance, a mangrove forest potentially provides ecosystem services like flood protection, fish nursery, collection place, aesthetics, or sacredness to local peasants and fishermen, and prevents new harbours, shrimps industry, ship breaking, etc. which have different value to different people(s). Which potential is realised is a matter of power, and of societal/political conflict moderation processes; environmental conflicts begin HERE.

The currently used ESS definition and the corresponding cascade hide these processes and – in the worst of cases – can support or even legitimate ignoring them. For some examples how markets can change the use value attribution of indigenous groups and thus their land management, see Spangenberg et al. 2014a.

Trade-offs between beneficiaries – the cause of political conflicts and environmental injustice

Mobilisation: who has the right to access and mobilise a potential service? What constitutes a right (tradition, labour, contracts, payments to whom)? Are collective and traditional rights acknowledged?

Appropriation and distributional justice: Who takes what, services and disservices? Who provides distributional justice? Who makes polluters pay, and is payment the right compensation? Is compensation possible at all?

Commercialisation can provide income, reputation, tax, and more, but also the erosion of tradition and culture. See (free of charge) Spangenberg et al. 2014b how market mechanisms have eroded traditional cultures and their achievements.

Some conclusions

Use value attribution is a matter of power, as is ESS appropriation; most environmental conflicts can be read as conflicts over use value attribution, ESS mobilisation and appropriation.

Considering ESS free gifts of nature is biologism, ignoring the social, economic and political processes shaping ESS definition, generation & distribution. Current ESS research, by neglecting social and political processes, non-economic values and the influence of power relations risk to generate pseudo-”objective” results serving the legitimation of dominant interests.

A political economy based revision of the ESS concept is necessary to avoid such effects. Taking social processes and environmental justice into account would avoid the naturalistic fallacy in the ESS concept and help mainstreaming and legitimising environmental justice concerns.

See for more details:

Spangenberg JH, von Haaren C, Settele J. 2014a. The Ecosystem Service Cascade: further developing the metaphor. Ecological Economics 104: 22–32. (no open access, sorry) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.04.025.

Spangenberg et al. 2014b. Provision of ecosystem services is determined by human agency, not ecosystem functions. Four case studies. Int. J. Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management 10(1): 40-53. Free download from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21513732.2014.884166#.U1qsSPk74eg

The project ENVJUSTICE has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 695446)