By Joan Martinez-Alier

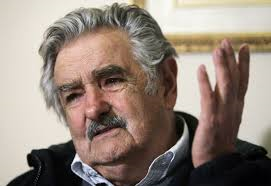

President Pepe Mujica has certainly deserved sympathy for his historical path as a former imprisoned tupamaro (a left-wing liberation movement), his sense of humor and the modesty in his lifestyle. But his government is preparing to radically change Mujica’s image to that of another megalomaniac miner – a Latin American left wing president who becomes a fervent anti-environmentalist. He is attracted by the huge scale and the money to be made from a project named Aratirí, for extracting and exporting 18 million tons of iron per year, almost 6 tons per inhabitant of Uruguay, about 15 kilos a day. There is a contract to be signed with Mr. Pramod Agarwal, the Indian owner of the Zamin company.

Meanwhile, environmentalists call for a referendum. On January 8, 2014 the Movimiento pro Plebiscito Nacional Uruguay Libre de Minería Metalífera a Cielo Abierto (The Movement for a National Plebiscite on Free Uruguay of Open Cast Metal Mining) gave a press conference against the signature of the investment contract between the national government and Zamin on the Aratirí project. They questioned the constitutionality of the new Mining Law of for large scale projects.

The Zamin company presents itself as an independent mining company with a world-class portfolio of iron mining projects in South America (Brazil and Uruguay), Africa, Australia and Asia. Its strategy is to become a leading producer of iron and coal for the global steel industry and also for precious metals and energy. They’re like the Three Kings or a Santa Claus from the Orient that come to take away the iron at a gift price.

The idea of the government is to sign an investment contract before completing the environmental impact studies. In addition, the idea is that environmental permits can be split: first for the mines, months later for the transport and only then for the big harbor. But if the project is stopped for environmental reasons or by the municipalities, will Zamin sue Uruguay?

The project would create 4000 hectares of open pits, with an area of direct influence of more than 100 thousand hectares, a mineral ore duct to the sea of over 200 kilometers long, and a large specialized harbor. The location of the latter has already changed twice in the plans. There is no environmental license yet. It would be an investment of 2 billion dollars for a period of 20 years. Environmental liabilities and environmental debts are not calculated.

At the end of 2013, it was assured in Uruguay that the Aratirí project, far from causing damage, would improve the overall environmental quality through appropriate investments with the money that it would generate. The government ensures that part of the income will go to an intergenerational fund for infrastructure and education.

With government support, the Swiss-Anglo-Indian multinational company Zamin Ferrous started prospecting the center of the country in 2007, affecting two towns: Valentines and Cerro Chato. The fields are settled by families of farmers for generations, in properties of 350 hectares on average. The land consisting of low wooded hills are used for livestock. The large open-pit mining will cause the displacement of families along with the devastation of the original ecosystem. The area has the Valentin Grande and Las Palmas streams that will be dammed for the exploitation of the mine, as the project requires large volumes of water.

In 2011, President Mujica analyzed the possibility of holding a referendum on this issue, but it was not carried out. To the contrary, Mujica prompted a new mining law, which opponents claim goes against the constitution. News in January 2014 is contradictory. On the one hand, there are ministers who announce the imminent signing of the contract. On the other, the possibility for a referendum seems open. President Mujica stressed the importance of investing in Aratirí, while acknowledging (graciously) that there is uncertainty about how the situation of the fields where iron would be extracted after the mine closes down. There will certainly be huge amounts of slag and tailings.

On December 2, 2013 a campaign to collect signatures was launched to ensure that a referendum or plebiscite takes place to ban open-pit mining. This requires, before the end of April, some 260 thousand signatures. Zamin opponents want the ban of the exploitation of metallic minerals in open pits. They add: This way we would be in the same situation as Costa Rica. It’s better to ban it before signing the contract to avoid what is happening now in Costa Rica, where the Canadian company Infinito Gold claims compensation for the cancellation of the Crucitas project.

The project ENVJUSTICE has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 695446)