By Shareen Elnaschie

The remote region of Anosy in southeast Madagascar has been undergoing significant and rapid change due to mining-led development that has been clashing with local culture, stimulating dramatic shifts in the relationship that local communities have with their land. In 2005, QMM (a partnership organization between Rio Tinto and the Government of Madagascar) began operating one of three planned mines for ilmenite, a source for titanium. QMM leased 6,000 ha of land for ilmenite extraction. 12% of this was donated to conservation and an additional 31,275 ha were committed outside of the mine site for biodiversity offsets. These drastic adjustments in land availability have resulted in widespread displacement that is threatening traditional ways of life and stability in the area. As has been previously reported, protests in Toalagnaro in 2011 destroyed nearly 200 homes and in January 2013, locals trapped 180 mineworkers at the Mandena mine site. In addition to displacement, both physical and economic, these protests have largely been a reaction to an ongoing lack of employment, poor community engagement processes and contested compensation rates and strategies.

Conservation is a critical issue in Madagascar: 80% of species are endemic, 80% of the island is deforested and in the southeast region, only 10% of original coastal littoral forest remains. The need to protect what little is left is clear. However, for poor rural communities who rely heavily on forest resources, any alterations to their access have dramatic effects on their livelihoods, food security and culture. Many have criticized QMM for manipulating this paradox to their advantage, using conservation as a key component of their land access strategy.

Compensation and benefits have long been utilized as the primary tools to mitigate the negative effects of development projects. However, with ever more complex mitigation strategies, the line between these two concepts is blurring. With attention focused on environmental damages, communities are left vulnerable and under-compensated. Although guidelines do exist, they are open to interpretation and manipulation. Rio Tinto’s own definitions state that ‘compensation equals payment for what (they) take away’, equaling the value of the loss, and ‘benefits are where (they) add value’, constituting ‘the extra things that developers can offer as a result of opportunities created by the developer’ (Rio Tinto, 2012: 3).

In QMM’s Social and Environmental Impact Assessment (SEIA), the removal of forest for mining was justified because it was assessed that the ‘remaining forest would have gone in 20 years anyway’ due to local use (Seagle, C., 2012: 449). QMM relies on this to justify both the degradation of forest through mining and the need to create conservation zones necessary to offset the damage caused. This effectively re-packages essential offsets as project benefits in order for QMM to appear more like a responsible developer. Many complaints were raised by international groups that assessed the SEIA, most significantly that measurement systems did not consider local values placed on land, seek local knowledge when making assessments on forest cover or sufficiently consider customary land rights. Throughout Madagascar’s long history of colonial interventions there has been a focus on formal access systems at the expense of customary recognition, leaving many communities vulnerable. Rival claimants who understand the process of titling may be favoured by the state, or in the case of development led displacement, those still relying on customary systems may not be deemed eligible for full and fair compensation.

In this way, QMM has translated its responses from compensation necessary to offset mining activities, to benefits produced by a developer. Other, supposedly community-led and environmentally responsible project ‘benefits’ introduced, include eucalyptus re-forestation projects and the promotion of eco-tourism in the area based on the cruise ship industry. Through a process of sustainability discourse manipulation and ‘discursive domination’ as described by Hajer, (1995: 60-61), QMM has effectively transformed the view of its ‘land access and legitimization strategies’ (Seagle, C., 2011: 15).

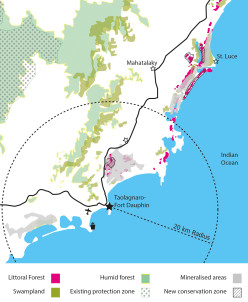

Figure 1 shows the spatial consequences of QMM’s mining activities. Restricted access to land and forest resources, justified by conservationist and sustainable development goals, become rigid forest management schemes that essentially criminalize traditional activities and are enforced with fines that further impoverish affected communities.

Displacement, both physical and economic, is a phenomenon experienced by increasing numbers of marginalised populations, caught between the drive for economic growth (with increased social metabolism) and the need to protect existing biological environments and cultural landscapes. Attempts to simultaneously extract and protect resources result in the rapid removal of vast amounts of land from community use. Current development models aim to mitigate and offset these effects through compensatory and conservation responses but typically these do not address the complex link between community vulnerability and ecosystem vulnerability. These inadequate responses inevitably lead to ecological distribution conflicts; they stem from the way that differing value systems are deployed in development projects.

The people of Anosy, like many rural communities, have a strong connection with the environment and give significant value to this socio-ecological relationship, a critical aspect of their resilience. This resilience is eroded first by land grabbing and then by the very schemes aiming to enhance conservation. What are we protecting, why, and for whom?

References:

http://www.envjustice.org/2013/03/rio-tinto-in-madagascar-15-activists-arrested/

http://www.envjustice.org/2013/01/madagascar-local-protests-against-rio-tinto/

Hajer, M. (1995). The politics of environmental discourse. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Rio Tinto (2012). Compensation and benefits for land access guidance. [report] Rio Tinto.

Seagle, C. (2011). The mining-conservation nexus Rio Tinto, development ‘gifts’ and contested compensation in Madagascar. LDPI Working Paper 11. [report] LDPI: Land Deal Politics Initiative.

Seagle, C. (2012). Inverting the Impacts Mining, conservation and sustainability claims near the Rio Tinto/QMM ilmenite mine in Southeast Madagascar. Journal of Peasant Studies. [report] 39: 2, 447-477.

This article is based on Shareen Elnaschie’s 2013 master thesis Discussions on Languages of Valuation and Compensation: the case of mining in southeast Madagascar written for Master of International Cooperation: Sustainable Emergency Architecture at Universitat Internacional de Catalunya.

Pingback: Former student highlights compensation manipulation in southeast Madagascar :: Master of International Cooperation Sustainable Emergency Architecture

Good questioning and nice to remind us that we are connected to nature. But then, how could the “complex link community and ecosystem vulnerability” be better addressed, and human needs better cared for ? Any recommendations for corrrection/remediation, even in very, very general lines, from now on ? Or could QMM have done better from start ?

Hi Eric,

Thanks for your questions!

I am obviously simplifying and there is much, much more that can be said, however…to better address the link between community and ecosystem vulnerability, I think we need to put much more effort into establishing a common language of valuation prior to undertaking research; SEIAs, for example. This means engaging with the community at a much earlier stage to establish systems of measurement to ensure that assessments take into consideration all aspects of the communities’ reliance upon the habitat, to understand traditional land management tools, and to put measures in place to build upon and support these existing networks. These approaches essentially prioritise community resilience in order to safeguard the ecosystem and potentially reduce the need for compensation.

Correction and remediation suggests that damage can be undone and I’m not sure that is possible at this stage. However, I think serious consideration needs to be given to the alternative livelihoods programs being initiated as project ‘benefits’. Rather than focusing on those that either have dual benefits for the business, or that QMM believe make them sound sustainable, more attention should be given to those already in existence, such as artisanal mining, for example. This is a booming business that holds much potential if supported effectively and may also help to ease some of the pressures of increased migration to the region that has inevitably resulted from QMMs presence.

Could QMM have done better from the start? Absolutely! But we also need to acknowledge the restrictions of best practice guidelines- a point relevant not just to QMM but also to the World Bank and others, particularly when working in contexts of weak governance. We must also give greater recognition to customary land access rights (different from land ownership rights) and current categorisations in guidelines are not sufficient or flexible enough to support such varied systems.

I hope this goes some way to answering your questions.

Hi

This calculations of the compensation cited above should be done during the negotiation when signing the contracts of exploitation with QMM as a government duties! It was not done in time!

However, whatever we do the destruction of primal biodiversity will not be returned at its previous situation! And the compensation is not quite right to be discussed right now! Since QMM had the permit of exploitation, they undergo all subsidiaries questions! The lessons learned could be an advice s for the next coming mining sites!