By Arnim Scheidel, Daniela Del Bene, Juan Liu, Grettel Navas, Sara Mingorría, Federico Demaria, Sofía Avila, Brototi Roy, Irmak Ertör, Leah Temper, Joan Martinez-Alier.

A new article by the EnvJustice team at ICTA-UAB, based on the EJAtlas, presents the largest analysis of environmental conflicts up to date with findings that have direct implications for enhanced support of environmental defenders.

The article, published in Global Environmental Change, looks at nearly 3000 cases worldwide. There is a world movement for environmental justice, composed of a myriad of local movements against fossil fuels extraction, open cast mining, tree plantations, hydropower dams and other extractive industries, and also against waste disposal in the form of incineration or dumps.

This is the environmentalism of the poor and the indigenous. It took the name “environmental justice” in the South of the United States in the 1980s, from movements against the unjust, disproportionate socio-environmental impacts in areas predominantly inhabited by Black, Hispanic and Indigenous populations. Environmental defenders who protest destructive resource uses are indeed a promising force for global sustainability and environmental justice. However, their activism comes at a heavy cost: many face criminalization, violence and murder.

The bulk of the information on this movement comes from activists rather than academics. Activists such as OCMAL in Latin America (Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros) started to make maps of conflicts, as also OIlwatch and other organizations born in the 1980s and 1990s. Another civil society organization, Global Witness (and not a UN department or an academic organization), provides yearly figures and the names of environmental defenders killed defending the environment and their livelihoods. The world movement for environmental justice operates so far at the margins of the international meetings (the COPs) and the Panels (IPCC, IPBES) which occupy central spaces of information and propose public policies. This article is inspired by environmental grassroots movements across the world, and it aspires to support them by making their activities, their failures and successes, more visible. As academics our research is supported by an ERC Advanced Grant (2016-21), with the title “A global environmental justice movement: the EJAtlas” (www.envjustice.org).

The open-access Environmental Justice Atlas (www.ejatlas.org) started at ICTA-UAB (Barcelona) in 2011 in a previous European-funded project, EJOLT. It has reached 3130 entries of ecological distribution conflicts by May 2020. Each entry contains a description, sources of information, and many codified variables. It is directed by Leah Temper and J. Martinez-Alier, coordinated by Daniela Del Bene, and it has counted with hundreds of collaborators. The authors of this article are among the main ones.

This article is a milestone in the field of statistical and comparative political ecology, possible through the global Atlas of Environmental Justice (www.ejatlas.org)

Highlights are:

-Why are there so many environmental conflicts worldwide?

-Environmental defenders, particularly indigenous peoples, often confront violence

-How often are such grassroots movements successful in defending the environment?

We present quantitative analyses shedding light on the characteristics of environmental conflicts and the environmental defenders involved, as well as on successful mobilization strategies.

Environmental defenders are frequently members of vulnerable groups who employ largely non-violent protest forms. In 11% of cases globally, they contributed to halt environmentally destructive and socially conflictive projects, defending the environment and livelihoods. Combining strategies of preventive mobilization, protest diversification and litigation can increase this success rate significantly to up to 27%.

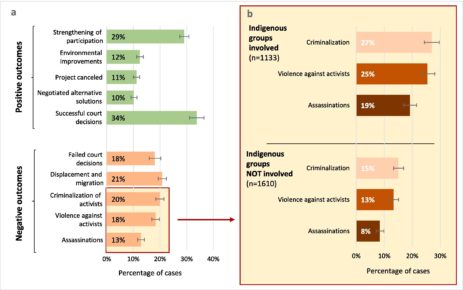

However, defenders face globally also high rates of criminalization (20% of cases), physical violence (18%), and assassinations (13%), which significantly increase when Indigenous people are involved (see image below).

We find that bottom-up mobilizations for more sustainable and socially just uses of the environment occur worldwide across countries in all income groups, testifying to the existence of various forms of grassroots environmentalism as a promising force for sustainability.

Full article: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102104

The project ENVJUSTICE has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 695446)