By Julie Snorek.

Mali is one of the least developed countries in the world, with nearly half the population living near the poverty line. In the past six years, the country has experienced civil war, jihadist terrorism and a coup d’etât. More than 500,000 Malians have fled the instability and violence.

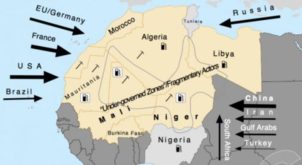

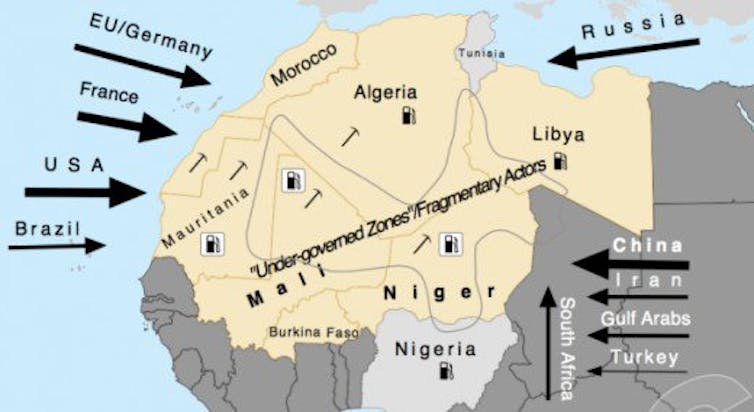

Supported by France and the US, a coalition of Sahelian states – called the G5 – have been mobilised by the UN Security Council to secure Mali from jihadist advances. At stake for all these multinational forces are also wider interests of regional stability, including petroleum and mineral resources.

Despite the increased militarisation of the country, jihadist insurgents continue to attack multiple Western and military outposts. This in turn has increased the need for their continued intervention.

Adding to the complex security mix is the fact that multinational companies are exploring petroleum reserves in Mali’s Taoudeni Basin. The basin stretches from Mali’s northern borders with Algeria and Mauritania southward to the river Niger – it contains vast oil and gas reserves. Estimates drawn up in 2015 suggest that Taoudeni has petroleum resources on a par with Algeria.

For the past four years Mali’s central government in Bamako has encouraged exploration of the basin. This suggests that a certain threshold of stability has been achieved and that the government believes that oil exploration can contribute to the region’s long term stability.

The reality is that it’s likely to do the opposite and fuel tensions rather than ease them. Fears that oil exploration will exacerbate tensions are based on the fact that oil companies need protection from the government and its partners to able to operate. This is likely to mean using foreign military forces to protect commercial activities.

Jihadist groups

The French have engaged in counter terrorism in the region since January 2013. Their original operation emptied Mali’s main cities of Al Qaïda of the Islamic Maghreb and other groups that had taken over during the 2012 civil war. But it failed to weaken the jihadist groups.

France now has 4,000 troops contributing to the G5’s 5,000 . There is also an American drone base, a UN peacekeeping force and the US has trained the Malian army. All have contributed to Mali becoming increasingly dependent on external forces to keep the peace.

Yet even with more sophisticated fire power, the military has failed to stem the growth of terror groups or prevent attacks. Jihadist groups seem to be garnering greater influence over local populations and thus greater permanence in the region. This is in part due to the fact that it serves as an alternative to the failing Malian government in some regions.

Since 2012, two groups are reported to control the northern part of the region. These include the Coordination of the Azawad Movement and Al-Qaïda of the Islamic Maghreb, and they have highly contradictory priorities.

The Coordination of the Azawad Movement is a secular movement responding to the marginalisation of Northern Mali and is a coalition of armed groups that rose up after the 2012 rebellion. The group was party of the May 2015 Algiers Peace Accords that attempted to end Mali’s three year-long civil war. Through these discussions, the group requested that 20% of the region’s energy and mineral production be reinvested in northern Mali.

In contrast, Al-Qaïda hopes to reinstate the Islamic Maghreb and rule the region as the caliphates did in the Middle Ages. To achieve this goal, the group has terrorised western symbols like the attack on a popular hotel in Bamako in 2015.

Oil development in the Basin

Since the first test wells were drilled in the 1970s the region has been perceived as a “last frontier” of unexplored West African oil. In 2004 the government under president Amadou Toumani Touré injected new energy into exploration efforts in a bid to become a member of Africa’s petroleum club. New petroleum legislation was passed and nearly 700,000 sq kms was carved up into 29 blocks across the country. These were offered as shared concessions to foreign petroleum companies.

So far over 15 companies from Australia, Canada, the US, Ireland, United Arab Emirates (UAE), France, Spain, Italy and Qatar have been involved in activities in what has become known as “the El Dorado” of petroleum reserves.

Over the past four years the Mali government has also made a concerted effort to invest in the northern regions. Under programmes like the “emergency development programme for the northern regions” nearly $180 million has been put into the most vulnerable communities. Money has been primarily targeted at much-needed infrastructure.

It’s possible that petroleum earnings and the development plans may eventually contribute to peace and stability in the north of the country.

But it’s equally plausible that petroleum development could lead to a resource curse. This refers to situations in which government coffers are filled with petro dollars, none of which is invested in the communities where the oil is being extracted. The impact for local communities is often land degradation, a greater distrust of institutions and further disenfranchisement.

To avoid the resource curse and to map a more credible road to peace in the region, the focus should rather be on building the capacity of local communities to have a greater say in how the oil extraction can be pursued. And how the proceeds can be more equitably distributed.

This article was first published at The Conversation.

The project ENVJUSTICE has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 695446)