By Nick Meynen.

Since 1996, the regional government of Flanders has been trying to build a new highway that would close the ring road around Antwerp. Despite the name, the existing ring road does not go around the city but runs through the city, due to urban sprawl over the last century. The air pollution in Antwerp is some of the worst in Europe and life-expectancy is below the regional average. The huge new project would intensify the problem. The most controversial part is a 3rd highway crossing under the river Schelde and the increase of traffic in the city. Now, architects, doctors, democracy activists and campaigners have united to promote an alternative. It has taken Antwerp by storm and will influence the upcoming regional elections, slated for May 25.

Another Unnecessary Imposed Mega Project[i]

The project costs have ballooned from an original 0,55 billion euro in 2000 to 4,9 billion euro currently. The BAM (Beheersmaatschapij Antwerpen Mobiel) – a state vehicle set up to execute the works – still claims it costs 3,2 billion euro but from an undisclosed section of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) with details on prices in contracts, it becomes clear that the costs are 4,9 billion euro. A green MP used his right to information to see the undisclosed information. Then he broke his pledge of secrecy to unveil that the figures had been manipulated.

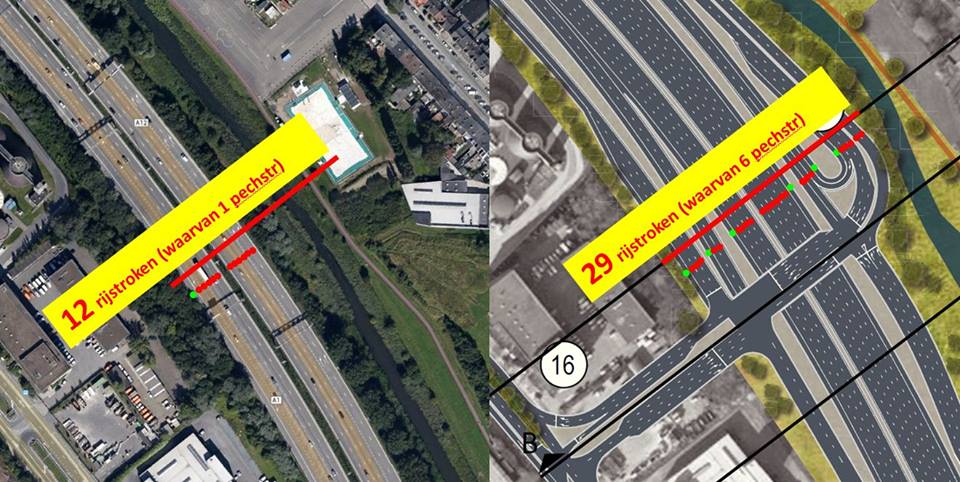

A direct consequence of the closing of the ring road at the place proposed by the BAM is that the ring road will need to increase capacity to up to 18 lanes (9 on either side). In some places, capacity would go from 12 to 29 lanes, for a total of 130m of highway. See picture.

The tunnel the BAM proposes is only for a small stretch in the harbor and in the latest twist of their plan they will also replace a viaduct in Merksem with a highway under the horizon line – but most of the new ring road will remain in open air. The 150.000 people that live less than 500 meter away from the highway will continue to live in air pollution levels considered way too high by the World Health Organisation and in some places it will even get worse. How the Flemish government thinks to get away with this when the European Commission already referred the government to the European Court for failing to meet standards on concentrations of fine particles in the air, remains a mystery.

The government first hoped that political cost of the project and its negative impacts would be minimal – as the biggest disadvantages would disproportionally hurt neighborhoods with above average immigrants and low voter turnout, located in the North part of the city, bordering the harbor. But they were wrong.

Plan B for A[ii]

Resistance has been widespread and comes mostly from four groups:

• Since 2005: StRaten-generaal: a democracy advocacy group of concerned citizens.

• Since 2008: Ademloos: a group of health experts concerned about health impacts of air pollution

• Since 2012: Stramien: urban developers who worked out a plan B: ‘Uit de ban van de Ring’

• Since 2014: Ringland: a citizen movement to implement Stramien’s plan

These 4 groups work together and support each other. In 2009, stRaten-generaal and Ademloos managed to collect enough signatures to force the city of Antwerp to hold a referendum. The referendum question was yes or no for the BAM-track, the route proposed by the government. On 18 October 2009, the people of Antwerp voted no. The government decided to neglect the result of the referendum and go ahead with the BAM-track, although in a modified version. The route would remain the same, but an especially controversial bridge would be replaced with a tunnel.

The action group stRaten-generaal has developed alternative routes away from the city – which they have presented to some of the world’s leading urban development experts. In every independent comparison, their plan – the most recent one is called the meccano-track, comes out better. It puts the closing of the ring road in the harbor, away from the city and it directs traffic away from the ring road that runs through the city. Only the official EIA puts the BAM-track on top. However, most people who wrote the official EIA all work for the BAM, for several years. And the EIA has not compared the two alternatives using the same parameters, using toll in one scenario and no toll in another. For that reason, stRaten-generaal is already preparing a court case and they are very confident that they would win it.

The conflict is also a conflict between the health concerns of the 150.000 people living next to the highway and the mobility concerns of the rest of Flanders, who also use the highway to get from A to B. The EIA showed that the Meccano-track takes 3 minutes more than the BAM-track. In the past, action groups and commentators in the media have said that we have to choose between 3 minutes faster for the whole of Flanders or better health for the 150.000 people around the highway. While the BAM-track claims to improve overall liveability (based on air pollution and noise) by 20% and Meccano claims a 25% improvement – Ringland claims a 90% improvement in air pollution and close to 100% in noise pollution reduction. Which is a normal result of putting the whole ring road not just under the horizon line (as it is now in most parts) but under the ground.

The rise of Ringland

Since Ringland launched a campaign on facebook in February 2014, with a video explaining the plan from Stramien, a daily flag hoisting and another happy ringland video, the debate has taken a new twist. Mass mobilizations organized by stRaten-generaal and Ademloos pro Ringland occurred, with over 10.000 people.

The new group – Ringland – gained 15.000 supporters in just 3 months and is fast gaining cross-party support. Most political parties now say they support the plans of Ringland – because of the elections in 25 May. In Antwerp, opinion polls show a landslide from parties that approved the BAM-track to parties that have resisted it all the time. After many years of fighting a plan and resistance to something, people are relieved to be able to support something with positive energy and enthusiasm. The group refers to the Big Dig in Boston, the now capped ring road of Madrid, an ongoing project in Maastricht and plans for Hamburg amid calls to do something similar.

The Ringland plan was developed by an urban development company – Stramien – that has emerged as a new stakeholder in this conflict – but it has only become a tool for mass mobilisation after a group of young people decided to build a campaign around it. Ademloos and stRaten-generaal both support Ringland because Ringland is compatible with the meccano-track but not with the BAM-track (due to EU regulations on highway connections). In fact, stRaten-generaal had already asked for a study to cap the ring road ten year ago, with “BorgerhouDt van Mensen” but they didn’t have the capacity to make an advanced 56p plan made by the leading architect and founder of Stramien.

So all action groups now ask to first get rid of the Bam-track (as demanded in the referendum in 2009 by the citizens of Antwerp) and start work on Ringland. The conflict has changed from a conflict over where to put a new highway to putting a roof on the existing one and re-organising traffic. Ringland doesn’t speak about a new highway at all – it talks about health and green urban development. Ringland wants to solve traffic congestion in a different way: not by building new roads but by organising traffic better – for example by separating local and regional traffic in this now underground highway and by implementing a payment per use system for all car traffic, like in London. That would also be used to pay for a new and integrated public transport network in order to further reduce car traffic. The public opinion shift in priorities in Antwerp from better mobility to better health and from more roads to less traffic has been remarkable and should be seen as a success in itself. The whole Ringland project would cost 1,9 billion euro, which should be compared with the 4,9 billion euro for BAM. In addition to that, Ringland will bring down the external cost of health care – while the BAM-track would further increase the health costs. According to Doctor Van Duppen, Ringland would be paid back in eight years time if you include the reductions in health costs associated with the ring road. Also not included is the additional value created when hundred hectares of ring road become a park – in the middle of a city of half a million people.

Political attempts at recuperation and damage control

However, this conflict is far from over. The Minister-President Kris Peeters desperately wants to start work on the BAM-track and then see what Ringland could mean for putting a roof on the new infrastructure. The conflict seems set to become an issue in the formation of a new government after the May 25 European elections. The surging green party has promised to make it a make or break issue and the socialists who approved the BAM track (they are in the Flemish government since many years) now say that Ringland is their priority. The liberals have also joined the action groups, but the two biggest political parties – the right wing Flemish nationalist and the Catholic center party – still favor the BAM-track.

The conflict is rising in intensity and might reach new heights if the next government decides to just go ahead with the current plan to build the BAM-track. People in Antwerp now have very high hopes and expectations. If the next government doesn’t meet them, there are several steps the action groups can and probably will take. These involve the existing legal options for participation that still exist, a second referendum (legally you can do one for each legislature on the same subject but since 2012 Antwerp has a new legislature) and a court case. Most stakeholders now say or admit (although some only in private) that the BAM-track will probably never be implemented. In any case, resistance seems set to continue and increase, while positive energy surrounding an alternative seems set to grow as well. The next government will have to choose between years of confrontation or a paradigm shift in the way it defines progress.

This case has now been added as an environmental conflict in our Atlas of Environmental Justice.

[i] Also see this http://www.envjustice.org/2013/08/third-european-forum-against-unnecessary-imposed-mega-projects-strengthening-the-bonds-strengthening-the-struggle/

[ii] Antwerp has a logo with just the letter A. In the local dialect, A means ‘you’.

The project ENVJUSTICE has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 695446)