By Amanda Blank

Twelve of the largest corporations in Europe submitted a letter to the European Commission (EC), urging them to adopt an “Innovation Principle” to be taken into full consideration during policy and legislative processes. The tone of the letter was concern for recent developments in risk management and regulatory policy that do not aid immediate economic stimulation. “Our concern is that the necessary balance of precaution and proportion is increasingly being replaced by a simple reliance on the precautionary principle and the avoidance of technological risk.” They claim that innovation is inherently about taking risks, and it is being stifled by regulatory restrictions that favor a precautionary approach. “…[R]isks need to be recognised, assessed and managed but they cannot be avoided, if society is to overcome important challenges such as food, water and energy security and sustainability.” Though these industrial concerns are valid and economic stimulation is imperative, there are several reasons why this letter is tainted and in itself demonstrates the one-sided nature of industry-involvement in policy.

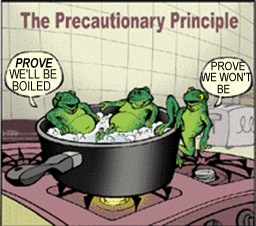

First and foremost, the precautionary principle does not squash or minimize innovation. Innovation may be a “risk-taking activity;” however, innovation should not imply making hasty decisions that may be destructive. “Innovation” has a positive association with the introduction of new ideas that generally benefit society. By introducing technologies that are not confirmed safe by scientists, highly negative consequences are possible–which diminishes the positive connotation of “innovation,”replacing it with “regret.” The precautionary principle takes overall societal health and well-being into account. This perhaps allows more innovation than taking unnecessary risks that may leave society worse off than prior to the “innovative” change. The report “Late Lessons from Early Warnings” that led to enshrining the current application of the precautionary principle highlights some of these, from asbestos to lead in gasoline and explains why business may not be in a position to take action even in the face of damaging impacts.

Second, the letter would be much stronger with scientific support. Do scientists believe we are being too stringent with the precautionary principle? If trusted scientists indeed believe the answer is yes, this letter would have more merit. In the Financial Times article, “Finding an element of trust,” the authors point out that the general public is often too distrustful of industry but say that we should have “open policy making,” which includes input from all sectors. Both of these points are valid. However, what the article fails to address is that industry most often votes for initiatives that will further their personal bottom lines, without sincere care for how society will be impacted. Industry presents very strong and open biases. When industry pushes for less precaution, we skeptics will ask: “What is their agenda?” Fundamentally, the precautionary principle is intended to protect society from detrimental errors, risks, and hazards that are unknown and unquantifiable. To reduce this in the name of immediate economic development or “innovative” industry defeats that purpose and consequently exposes society to mistakes that could have easily been avoided. The idea of implementing the precautionary principle is that it prioritizes societally-led innovation that is well-rooted in social needs. Therefore, innovation does not at all compete with precaution.

A key example of the EU’s usage of the precautionary principle is with genetic modification (GM) of crops. This is precisely the restriction implied by the corporations in the letter to the EC. “Finding an element of trust” claims that, “The problem people have with GMs seems to be one of business ethics. It is about multinational companies controlling our food and showing aggressive marketing behaviour.” Does the average person really think more about global business ethics than the immediate health of their family? It is hopeful to believe that the general publics’ primary skepticism of GM crops is business ethics, above a basic concern for potential health effects on their families. If the average person was that concerned about the global picture, our world would be a much more responsible place. Regardless, whatever the reason for taking precautions with our food system, the stakes are quite high. Corporate domination of the food supply, unpredictable allergens, and ecological collapse are a few of the potential outcomes of a GM-embracing world. These possibilities must be weighed against the benefits to the general public, which are still scientifically in debate. Using the precautionary principle is a not-so-earth-shattering method of policy-making, but a rather common sense approach.

The call for reduced restrictions highlights corporate agendas that go beyond the “economic stimulation for all!” façade. When industry is highly involved in policy-making, biases are strong and convolute the process. The corporate letter to the EC reasonably expresses interest in giving more attention to innovation, which is a noble goal. Let’s keep innovation and precaution linked together— to support creative solutions—without promoting unnecessary and potentially destructive risks.

Picture from: http://the-mound-of-sound.blogspot.fr/2013/01/the-precautionary-principle.html

great article! these companies are throwing up a smoke screen by using the the buzzword during an economically difficult time. innovation is wonderful and really important, and restrictions that call for safe and tested practices before they are used on a large scale don’t hinder it, they protect the environment, consumers and citizens.

Pingback: Late lessons from early warnings | ingmar schumacher

Nice post. But I do think the gov’t basically looks too little at the precautionary side:

http://wp.me/p3yx1u-77