by Joan Martinez-Alier and Leah Temper.

On 31st July 2013 in New Delhi drums and banners in front of Odisha House celebrated the success achieved by the tiny Dongria Kondh hamlets in the Niyamgiri Hill which, one after the other had openly expressed in the last days of July 2013 their refusal of open cast bauxite mining. One day later in London, there were demonstrations at the shareholders assembly of Vedanta Ltd (a London based mining and fossil fuels company) asking this company to quit the Niyamgiri Hill and the Lanjigarh alumina refinery in Odisha. Also, to stop forever iron ore mining in the Sesa mine in Goa. One of the organizations in London, Foil Vedanta, had said, “We will bring the defiant energy of the Dongria Kond tribe to London, as they fight the final stages of their 10 year battle for survival against Vedanta’s planned mega mine. Bring drums, placards, banners…”

In a precedent setting decision in April 2013, the Supreme Court applied the Forest Rights Act for the first time saying that it was up to the local communities to decide whether the project should go forward through public consultations and votes in each of the surrounding villages. After 8 villages have now voted against the project almost unanimously this July in the presence of judicial officers, it now seems as if the 10 year long struggle against bauxite mining in the Niyamgiri Hill has finally been won.

In August 2010, the Ministry of Forests and Environment had stopped Vedanta Ltd from its plans to mine bauxite at the top on the Niyamgiri Hill for processing in the nearby large Lanjigarh factory. After nominating a special committee of enquiry, the Saxena Committee, the Minister had agreed to its findings that Vedanta Ltd had infringed the Forest Right Act that protect especially the adivasi’s forests. The Minister did not say whether sacredness and livelihood should trump bauxite mining for industrial growth. His decision was based on technicalities. After appeals went to the Supreme Court, the decision was taken in April 2013 to resort to local consultations as provided by the law and carried out in July 2013.

The local opposition to bauxite mining in Odisha claimed that all hamlets should be consulted (over 200) but the authorities decided to consult only 12. Of these 12, the first eight have now openly voted against mining. Now, the remaining 4 villages will vote and reports will be filed, and it is likely that bauxite will not be mined in the Niyamgiri Hill. In a more distant future, we cannot know what might happen. A lot depends on political developments after the general elections of 2014.

Climbing the hill

There have been many struggles against bauxite mining in Odisha, both against state and private companies. Quite often they have been lost but not always. They have been narrated in Felix Padel’s and Samarendra Das’ thorough book (“Out of the Earth. East India’s Adivasis and the Aluminium Cartel”) and in the moving documentary Matiro Poko, Company Loko (Earth Worm, Company Man).

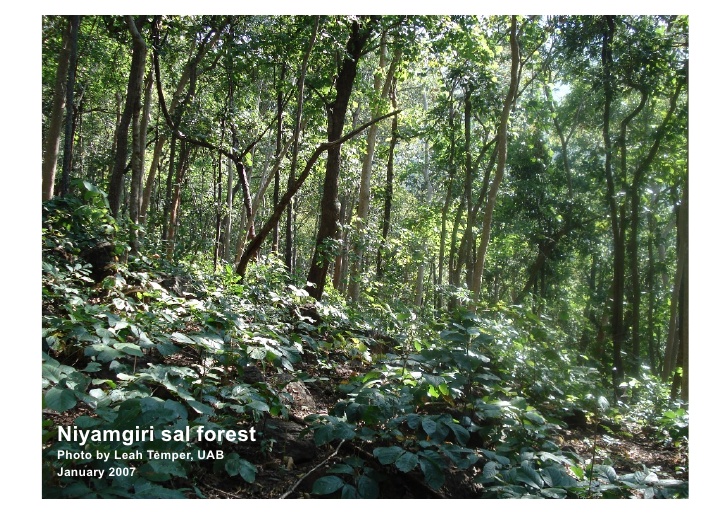

The first time we climbed the Niyamgiri Hill was quite early in the conflict, in December 2006. We also visited at this time and again on a second visit the village of Lanjigargh where Vedanta Ltd had prematurely built a one-million ton per year alumina factory (producing also two million tons of red mud waste), displacing some villages. The Lanjigarh factory has worked intermittently with costly and polluting bauxite coming by train and truck from distant places since Vedanta Ltd has until now not been able to get its hands on bauxite from the nearby Niyamgiri Hill. The Dongria Kondh said that the mountain was one important god in their pantheon.

A Glocal Conflict

Many academics, journalists and activists have visited the place. This has become indeed a “glocal” conflict. One wonders what is happening in so many other resource extraction conflicts around the world that are not even reported in the local newspapers. In that visit of 2006 we also went to Kalinganagar, an adivasi village where there was a massacre because of Tata’s plans for a steel plant. We wrote an article for the Economic and Political Weekly about such conflicts in Odissa and also in West Bengal, asking how could one compensate for the destruction of livelihoods and culture. “How much for your God, how much for the services provided by your God?” we asked.

A Dongria woman carries firewood

“The long battle over Niyamgiri throws up some knotty problems. For one, exactly how much of a veto can local communities have? In this case, can local people prevent the mining of any part of an entire range of hills on the basis of their religious beliefs? This is not a question of property rights, since the minerals underground are indisputably owned by the state, and the land above ground is not owned by the villages. Further, to what degree should religious belief play a role in such matters that are often decided on the basis of property law? While it is true that the Indian state has had a long history of exploiting tribal communities, and of not paying them a fair return for mining in their territories, it is unlikely that this will lead to allowing any community a veto on religious grounds over the use of large stretches of land in India that are under dispute for industrial and mining projects. Will communities that are not indigenous also be allowed to claim cultural rights over the landscape to stop “development” projects, such as the ongoing Posco Steel Plant conflict, also in Odisha.

Stopping the Juggernaut?

This coming 15 August Indian Independence Day will be celebrated. It has taken nearly seventy years for the Republic of India to fulfill the promises made to the Adivasis. In the assemblies in Niyamgiri Hill some Dongria Kondh said, you the Hindu non-tribal people worship Lord Jagannath, we worship the mountain, the god Niyamraja. The icon of the Hindu deity Jagannath is led in a procession every year in Puri, a coastal city in Odisha, in a chariot that is said to run sometimes over the faithful. Juggernaut was how the English spelled it. And indeed the world of the Adivasis in India has been run over by the Juggernaut of mining project, hydroelectric dams, eucalyptus plantations. Outsiders have encroached and entrenched themselves in many Adivasi areas, often exploiting their labour too. In states neighbouring Odisha and in some parts of Odisha itself they are caught in between the Naxalite rebellion and the state security forces. The Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act and the Forest Rights Act have been sometimes effective to safeguard Adivasi rights over their lands, as in the Ministry of Forests order of August 2010 and in the Supreme Court decision of 18th April 2013 for the Dongria Kondh. However, the increase in the social metabolism of the economy driven by economic growth has robbed the Adivasi and other rural peoples of their forests and the forests of their trees, people, animals, and soil. Against this, the attempts to put money values on environmental products and services of forests are often well intentioned by not effective in practice

Forest Valuation does not lead to justice

Recently, we have written another article on this case (a product of the EJOLT project) which will soon appear in the journal Ecological Economics. The article analyses the decisions of the Indian Supreme Court over the years on cases related to forest destruction by mining or hydroelectric or other land grabbing projects, all of them coming under the “Godavarman” umbrella from the name of the original case in Tamil Nadu. It discusses the well-intentioned work of the Kanchan Chopra committee in placing monetary values on environmental products and services from forests. Our article focuses then on the Niyamgiri Hill conflict. This is the title and summary

The God of the Mountain and Godavarman: Net Present Value, indigenous territorial rights and sacredness in one bauxite mining conflict in India.

This article provides an environmental and institutional history of the highly politized and contested process of setting a Net Present Value for forests in India, in a context of increasing conflicts over land for development, conservation and indigenous rights. Decision-making documents in the Supreme Court and in one specific case of a bauxite mining conflict involving Vedanta in the Niyamgiri hills are studied to come to conclusions about how pricing and commodification of forests has moved through the political process. We argue that establishing NPV for forests is not conducive to conservation, and it is not conducive either to environmental justice in response to land conflicts in India for the following three reasons.The technical and political process of setting prices deepens and reproduces structural inequalities with negative distributive effects. NPV encourages economistic decision-making procedures that exclude participation. Finally NPV does not recognize or take into account cultural difference or plural values. We thus conclude that economic valuation of forest products and services has not managed to “save” forests in India and is not an effective or viable strategy for environmental justice activism.

http://www.asianage.com/

The project ENVJUSTICE has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 695446)