*Turkish word now meaning “fighting for your rights” (see wiki).

The lack of consultation, the aggressive police intervention and the conversion of public space into private space explain why the occupation of Gezi park is not just meant to save trees, but to save Turkey’s democracy. But while that story covers the fast growth from a demonstration in a park in Istanbul to a nationwide revolt, it also hides a different reason for unrest: the nationwide assault on the environment. Here we will focus on the environmental justice angle of the protests.

The Gezi Park case is linked to other environmental conflicts in Turkey over urban enclosures and mega-projects (e.g. dam building, the third bridge, and the canal project) as well as over mining conflicts, nuclear conflicts and environmental degradation—many in areas that are ecologically quite sensitive and/or have high conservation value. No doubt, these conflicts, including the Gezi Park resistance, should be situated within the broader context of Turkey’s industrial metabolism, structural change and growth dynamics—which is one of EJOLT’s ultimate objectives. But let us first look at how events unfolded in the last two weeks.

How did it all start at Gezi Park?

For months now, a group of academics, architects, environmentalists and rights-based non-governmental organisations—known as the Taksim-Solidarity—have been protesting the plans to redesign Taksim Square under the rubric of a pedestrianisation project, and rebuild the Ottoman Military Barracks (Topçu Kışlası) that were once in Gezi Park and demolished in the 1930s. Gezi Park is the only green space left in Taksim, the busy centre of Istanbul’s European side. When news spread that bulldozers were moving in to uproot the park’s trees in preparation of the construction of the barracks, a group of activists occupied the park with tents and launched the hashtag #occupygezi on twitter calling out for support. More and more people joined the protestors in the park, which turned the Park into a socially and ideologically diverse solidarity arena.

The tension suddenly amplified on the third and fourth days of the peaceful sit-in (30-31 May, 2013) when police charged the protestors at 5 AM both mornings, dismantling and burning their tents, and attacking them with teargas. The violent attack was filmed by one of the protestors and immediately shared on social media. The sheer brutality and oppression of the police and the shameful silence of the mainstream media provoked the general public, and within hours, a peaceful sit-in to prevent the destruction of trees snowballed into a nationwide anti-government protest. Crowds chanted “everywhere is Taksim, resistance everywhere” while being subjected to water cannons, pepper spray and teargas.

In the absence of conventional media coverage, the usage of social media soared. Twitter proved itself as the main platform to share ideas, images, and uncensored information, and helped protestors secure strategic positions in clashes against the police. Certain statistics show that 2 million tweets were sent in 8 hours on May 31, and by Wednesday, June 5, a total of 14 million tweets had been sent. One graffiti in particular describes the situation and twitter as being the only remaining tool for protesters to access correct information: “The revolution will not be televised, it will be tweeted!”

In a series of increasingly aggressive speeches, PM Erdogan made clear that his plans to demolish Gezi Park and rebuild the Ottoman Barracks were unalterable. His statements ignored the demands of millions and unveiled his characterisation of the protestors: “We are decided; we will build the Ottoman Barracks. The words of a couple of ‘capulcu’ are irrelevant”. Capulcu means looters, plunders or marauders in Turkish, and was very quickly adopted by the demonstrators. “Chappulling” is now popularly used during protests and in social media to mean “fighting for your rights”.

Ottoman Military Barracks for what?

While the conflict is exacerbating, there are still some speculations about the plan, and the role that the building can play in Taksim. What would be its function? How might it contribute to the urban life of Istanbulites? No-one seems to have any answers. The most we can tell is that PM Erdogan is still undecided—not about its construction, but its function. Early this year, he said that the construction plans contained a residential area and a shopping mall. Later, he announced that Istanbul was a world-class metropolis that had too few luxury hotels, and so the reconstructed building should be a hotel, around which there would necessarily be some shops, a carpet store, for instance. He lately thinks that the building could serve as a city museum.

The plans for Taksim Square and Gezi Park should be seen alongside the process of appropriating public space for private and/or business ends; a phenomenon largely driven by rising real-estate prices and speculation in the city. The increasingly commodified urban space in Istanbul had already become an arena of social and economic contestation. Some well-known examples include the displacement of Sulukule residents from their neighbourhood, a predominantly Roma district located in the historical peninsula of Istanbul, as part of an urban renewal program (Robins, 2011); the relocation and reorganisation of Istanbul’s most popular weekly open-air markets in the context of a modernisation discourse that promotes “the hygienic city” (Eder and Oz, 2012); and tearing down the historical movie theatre Emek as part of a shopping mall construction (the Guardian, April 2013). Indeed, the enclosure of urban commons as a problem itself crystallised in the Gezi Park case even more, where the shared belief of the general public is strong as it is obvious that the people in Istanbul have no need of yet another shopping mall or a luxury hotel there, but instead are desperate for a public green space that they may commonly use with no social exclusion.

While PM Erdogan says protests will not stop construction plans for the park, Taksim Solidarity issued the following demands and requested concrete measures from the government (for a poster, click here):

-

Gezi Park must stay as a park. An official announcement must be made saying that Taksim Gezi Park will not be converted to a ‘Topçu Kışlası’ or any other building and the project is cancelled.

-

Governors and the police chiefs, and anyone who ordered, enforced or implemented violent repression tactics must resign.

-

Teargas bombs and other similar materials must be prohibited.

-

Detained citizens must be released immediately.

-

The prohibition of meetings, rallies, demonstrations and de facto hindrance in the squares and public areas across the country, starting with Taksim as a demonstration area for Labor Day (1 May), and Kızılay [Ankara] must be stopped; obstacles to freedom of speech must be lifted.

Environmental justice for the Gezi Park protestors

Justice claims of the Gezi Park protestors seem straightforward and in line with the global environmental justice movement. First, people claim a right to environment conservation and the preservation of cultural integrity. This is about a public park and a historical square, important to people not only for its trees, but also for its political and social past. As Çağlar Keyder notes, the square has been symbolic of Turkey’s Western aspirations, with official ceremonies and demonstrations, including May Day, being held there.

Second, urbanites want recognition and respect for their diversity, how they experience city life and what they expect from it. The government has been reluctant to acknowledge the plurality of needs and preferences in the country, and as Elif Şafak notes, numerous critical voices have been pushed to the margins in recent years; self-censorship was not uncommon. Third, people in the Park demand the right to participate in decision-making on matters related to local development and the environment. In the Gezi Park case, the government imposed a plan that involved Taksim Square and the park—public spaces in the minds of millions—without proper public debate. Here, the issue was not merely about not being consulted, but also the lack of involvement in decision-making, and the lack of transparency of the processes.

While these justice claims were not new to Turkey, the unification and complementary use of old and new means of protest for activism was novel. The crowds pouring into the centre included many young university students, members of the middle-class, and women. Some called themselves part-time revolutionaries, as went to work during the day with their suits and then took to the streets at night.

The classic protest methods included gathering in big public squares and holding demonstrations, while simultaneously barricading streets to prevent police forces from accessing Taksim Square. Clashes with the police meant shops ran out of gas and dust masks quickly, and pharmacies depleted their antacid stocks, used to make solutions to lessen the impacts of teargas and pepper gas. About a thousand people from the Anatolian side of Istanbul marched across the Bosphorus Bridge, and blocked traffic while heading towards Taksim Square. Labour unions also went on strike to protest the Gezi Park incidents. Judicial activism also came to the fore, and an appeals court has presently suspended the project to further investigate the issue; a definitive decision is yet to come.

Novel means of protest involved activists’ use of social media in exceedingly creative ways that within hours carried the protests beyond the Park, beyond Istanbul and even beyond Turkey. PM Erdogan’s use of the label capulcu inspired and helped people open up their minds. The protests are still accompanied by an incredibly rich sense of humour, as may be seen in the avalanche of humorous videos, slogans and graffiti (see the link for a selection). In the face of the Turkish government’s media blackout, it did not take long for the activists to set up lifestream accounts of the demonstrations and create their own Tumblr pages dedicated to images from their clashes with the police. Uploading music videos to social networking sites reinforced this sense of collaboration and sharing among protesters on streets and on their computers. Any available information was quickly translated into English and disseminated to the international media as well.

The Turkish police force is famous for their brutality in dealing with demonstrations and so protestors have had to deal with various pressures, such as extreme violence and arrests. The government has spent great effort to intimidate universities, business groups, hospitals and hotels that supported the protestors and protected them from teargas and other chemical attacks. According to a report by the Ankara Chamber of Physicians, three people died in demonstrations and thousands have been injured, some severely. Dozens were taken into custody for ‘inciting riots’ using social media.

Who is a better environmentalist?

Interestingly, the “tree revolution” happened in a country where the environmentalist discourse is very much dominated by planting trees and the nostalgia of living surrounded by nature in metropolitan Istanbul. PM Erdogan had already proclaimed himself a fervent environmentalist while lashing out against people protesting small-scale hydroelectric power plants in the North-eastern Anatolian and Black Sea regions. Choosing to base his argument on the number of trees planted, he used the Gezi Park incidents to remind people of this once again. While he sympathised with the people trying to protect trees, he said, “During the Justice and Development Party administration over the past decade, we planted almost 2.5 billion trees—(later corrected as 2.5 million)—in various age ranges all over Turkey. The ruling party is getting the job done well, and swiftly. As long as there are people interested in planting trees, there will be no problem. We are environmentalists. ”

Unsurprisingly, the booming residential development market adopted an environmentalist discourse as well. Real estate agents compete to greenwash their projects, and the first pages of newspapers are full of advertisements such as: “are you among those who can’t leave without sea”, “The nature will be next to your door?”, “You have never been so close to nature”. It was also very ironic to see that as Taksim Square was blanketed under teargas and pepper spray and people from all directions were pouring into Gezi Park, one of the most viewed private news stations was airing a documentary on penguins. The program ran uninterrupted while some of the most widespread anti-government protests the country has seen in modern times occurred.

The Gezi Park protests will surely make an immense contribution to the long-term struggle for environmental justice and sustainability. This tree revolution is expected to make a difference in Turkey’s demonstration culture, since the general public knows well that the protesters are cleaning the occupied park space and the neighbouring square and streets, in a peaceful manner every day.

As of today, June 12, PM Erdogan is insistent on building the barracks. On Tuesday morning, at 7.30 a.m. police marched into Taksim Square with water cannon vehicles, announcing they would not attack Gezi Park, but take down the banners and slogans (see the picture) from the AKM (the PM called them “scraps”). Suddenly, a group of 30 people charged at the police with Molotov cocktails and fireworks, and the police seemed mostly reluctant to prevent them. There are strong suspicions that this was basically a theatre set up to lend visuals to PM Erdogan’s accusation that protesters are vandals and looters. The majority of the protestors were peacefully sitting and waiting in Gezi Park. The human chain they formed between the police and the park was attacked by the police, who chased the people with Molotov cocktails with teargas; none of the TV stations showed this, preferring to broadcast the scene live from another angle. In the meantime, several dozen lawyers have been taken into custody for joining the ongoing protests.

Linking environmental conflicts with Turkey’s social metabolism

One of current arguments against the protests focuses on the extent of economic damage. Due to protests, many tourists cancelled their hotel reservations and the stock exchange rapidly fell in the early days. Pro-government economy columnist Yigit Bulut estimated the economic damage to be around $1 billion, and asked the public, “Are you happy now?” Indeed, for the general public in Istanbul, the trees at Gezi Park seem priceless. What is then the price of an apology for the government?

It is clearly crucial to place Gezi Park within a broader context. Since 1990s, Turkey has witnessed a growing number of environmental conflicts. While the size of the economy more than doubled in the past two decades, urbanization level rose from 60 percent to 75 percent and the population increased by 32 percent—all putting immense pressure on the ecological system of Turkey, a country with globally critical natural and biological reserves. The corresponding reaction in civil society has mainly manifested itself as environmental justice movements at the local and national scales. Over the past two decades, complaints against current or potential impacts from natural resource extraction, land use change, energy production and pollution have been very common and involved local communities at grassroots levels as well as national and international civil society organisations. People were fighting for their livelihoods, for their democratic right to live in a healthy environment, for the right to have a say in the decision-making processes of these energy, mining, water and urban transformation projects. Yet, as prominent economist Daron Acemoglu also notes, the steady and rapid economic growth of the last decade has not brought a higher level of democracy to the country. On the contrary, it came along with the suppression of justice claims and democratic rights.

Mainstream economists know that growth in Turkey is based on unsustainable levels of external borrowing and has not been particularly distinguished by emerging-market standards. In the meantime, we, as ecological economists and political ecologists, must unveil the driving forces that underlie the increasing number of environmental conflicts, and link them to increased social metabolism (in terms of energy and materials) and environmental indicators in Turkey.

The mega-projects that PM Erdogan proudly calls “Crazy Projects” are part of a growing extractive economy, and are seen as a way to soothe the structural problems of Turkey’s economy that has a large current account deficit and needs to attract large capital flows. These mega-projects include a third bridge over the Bosphorus Strait (which will destroy Istanbul’s last remaining forests), a third airport in Istanbul (supposed to become the world’s largest airport), two nuclear power plant projects, large-scale hydropower projects, and opening-up a huge channel to connect the Black and Marmara Seas.

Looking forward? Mapping Environmental Injustices in Turkey

These mega-projects, coupled with other “smaller” projects that are extractivist in nature (such as mining for minerals and building materials, small-scale hydropower projects, industrial waste disposal) clearly demonstrate that Turkey’s growth pattern is characterised by enclosure of public spaces (not only urban parks, but also national parks, forests, villages), extensive environmental degradation, and the subordination of environmental interests to those of national and international capital owners.

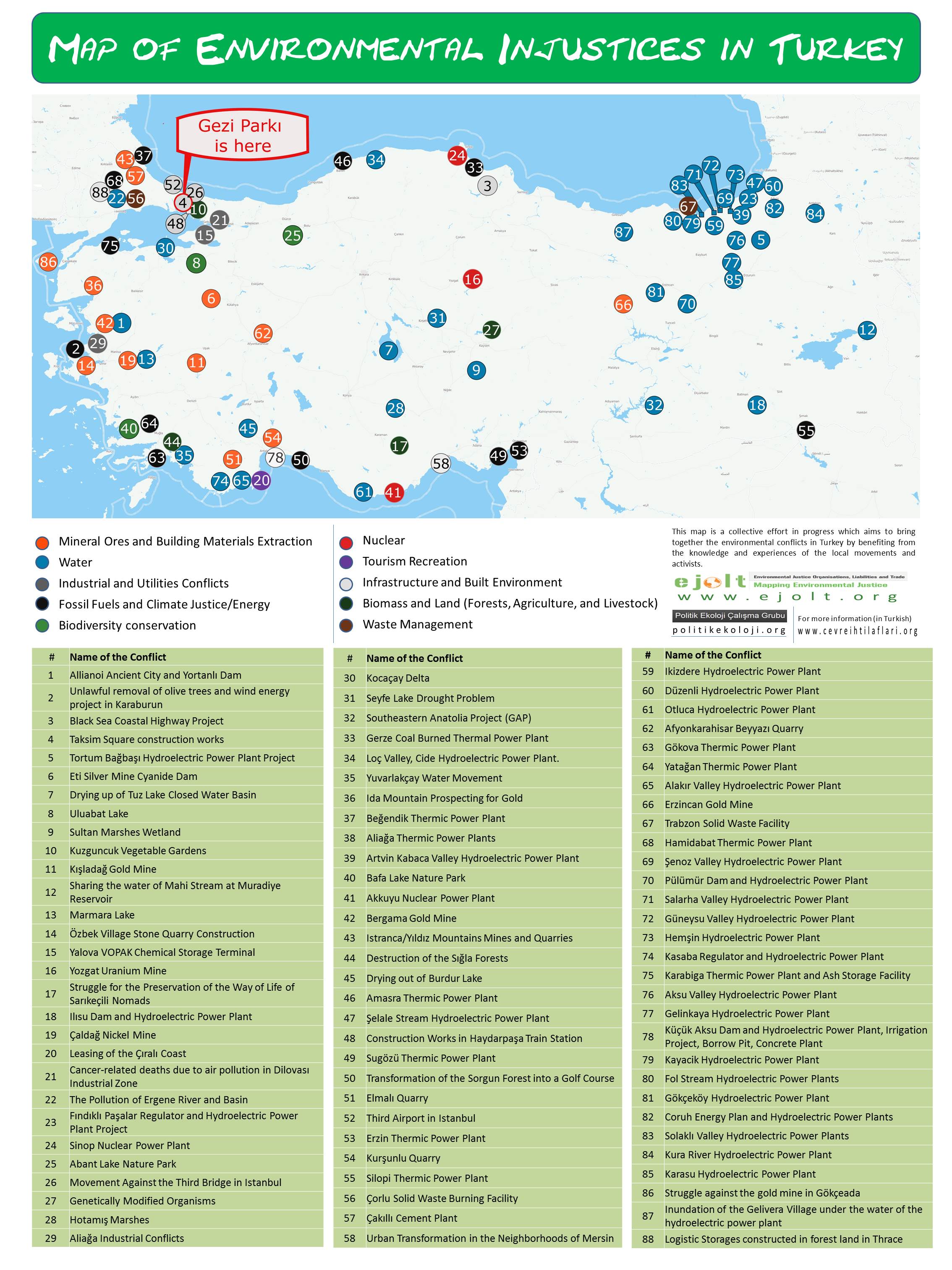

At this junction, we were reminded of the ecological distribution conflicts map we were engaged in thanks to EJOLT, and grew more aware of its significance. Even a very preliminary, incomplete map and list of environmental conflicts, which we called the “Map of Environmental Injustices in Turkey”, has attracted much attention. The cases selected for inclusion were chosen without concern for statistical representation, but to illustrate critical issues in environmental conflicts in Turkey. Some people asked us, “Why is our conflict not on the map?” The answer is clear: The map and our power to resist will grow as we gain more information and insight from the local and national environmental resistance movements.

Despite its limitations, the compilation of these cases will provide a basic, yet arguably very important step toward informing public debate in Turkey on the distribution of risks, burdens and benefits, and the claims of local communities expressed in different valuation languages within the development and environment nexus. In Turkey, the primary sources of tension in all these cases seems to be the presence of a highly modernist state ideology, as well as an unquestioned commitment to rapid economic growth combined with the absence of a deliberative planning process, a democratic scientific culture and a free press.

The challenge for the environmental movement in Turkey is to link local movements both to one another, and to an overarching national movement capable of robust and sustained action, with the aim of turning these conflicts into forces for environmental sustainability. We hope that this mapping exercise will increase the visibility of environmental justice struggles in a rapidly growing and globalising Turkey, and help activists to build networks, share knowhow, and access scientific research that is relevant to them and supportive of their arguments.

With hope and in solidarity!

Turkey EJOLT Team

Merhaba, hats off, your fight for nature and justice is inspiring. Wish you strength.

Thanks.

Great informative article! We need the new focus on environmental issues, and how grassroots politics and activism can constructively play a role against obsolete standards in the decipherment of such difficult situations.